Exhibition Review: Notions of Home at Yancey Richardson

Case Study House #21, 1960. Chromogenic print.© Julius Shulman, Courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Trust

By Madeleine Leddy

“Where are you from?”

It’s a question that few can say that they have never been asked. An icebreaker, a survey datum, a search for common ground—or, depending on the circumstances, a way of evaluating, and sometimes even insulting, someone. “Where you’re from” can hold connotations of everything from your ethnic origins to your social class.

The answer, for most people, is the place they call “home”—whether birthplace or more recently adopted “home”—a concept that, in an era where cross-border migration and travel are facts of daily life for more people than ever before, has acquired a blurred definition. The migrant, the traveller: they may identify with more than one place, have more than one “home.” And in some cases, when leaving one home behind is an involuntary act, they may adopt a temporary or transitory “home,” which will still never never be “where they’re from.”

Empire, refugee camp of Chouca, (Tunisia, 2012- 14). Archival pigment print. © Samuel Gratacap, courtesy of the artist, and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York

The “home-less,” too, have a place of origin—an answer or answers, however vague they may be, to the recurring question. All of these situations imply the existence of a “home,” past or present, and a “from,” which is necessarily in the past. And they are all plausible—which leads us to the conclusion that “home” and “from” may not coincide, but are often associated in our common conceptions.

The current installation at Yancey Richardson juxtaposes a smattering of situations on the “home” spectrum. And what a juxtaposition it is: on one wall hangs Samuel Gratacap’s oddly ethereal journalistic shot of UN refugee tents in the Tunisian desert; across from it, Julius Shulman’s “Case Study House #22,” an equally ethereal, film-noir-esque panorama of a very different, much less temporary kind of desert home—this one, a glass mansion perched over the Californian urban desert. One is meager, the other opulent—and yet both are desolate. Neither looks as though it could possibly “feel” like home.

Casper’s Last Naked, 2010. Chromogenic print.© Justine Kurland, courtesy of the artist and MitchellInnes & Nash, NY

The artists represented in “Notions of Home” are almost too diverse to compare stylistically, but the fil rouge of the exhibit is one of those inescapable qualities associated with home, or with place of origin: socioeconomic status. The featured photographers have captured nearly this entire spectrum of relationships between places and the people who live in them: from “homes” to “non-homes,” in a certain sense.

And the extravagance of the home, this spectrum seems to indicate, has little to do with how “homey” it actually is. The perfectly-coiffed model in Shulman’s glass Beverly Hills palace, for one, looks much less comfortable in her sterile fortress than Casper, the young, stark-naked boy in Justine Kurland’s image of a much more temporary—but still, though barely, functional—pillow-lined mobile home tucked away in an Appalachian grove. The mobile home is indicative of some level of human misery—akin, in this way, to the refugee tent in Gratacap’s image—but Casper’s easy pose on the ramshackle truck bed suggests that money and physical comfort aren’t what makes this home a home. He and whoever else lives with him, in this makeshift home, are bound to each other, and perhaps to the land on which they rove, more than they are to the ramshackle structure in which they, effectively, live.

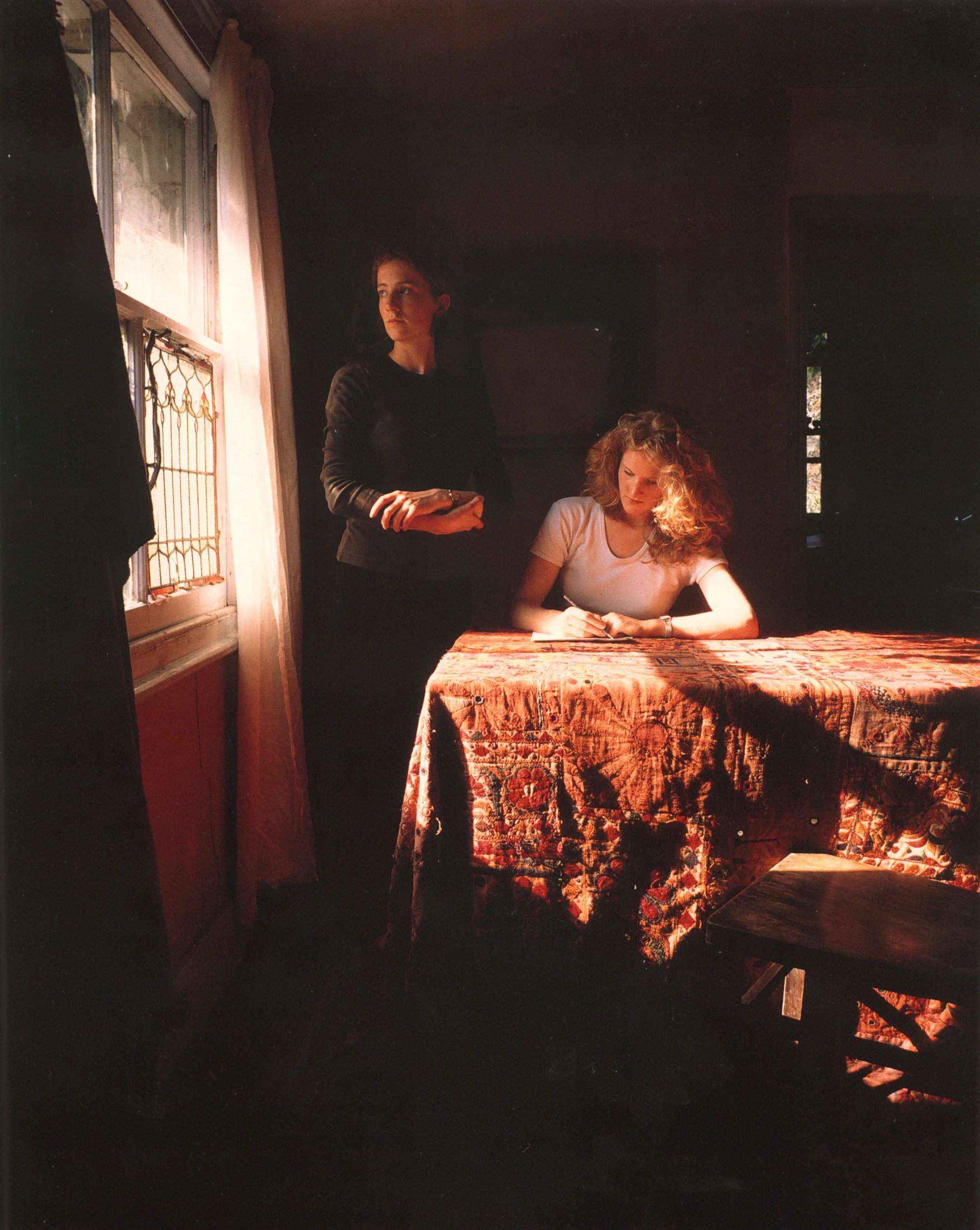

While nearly all of the works on display exhibit influences from premodern and early modern art—from Anthony Hernandez’s Cézannienne “Landscape for the Homeless #14” to Tom Hunter’s “Girl Writing an Affadavit,” which, in its middle-class costumery and chiaroscuro lighting, could be a photographic Vermeer—none do so without attempting to pinpoint notions of class. Indeed, Hernandez’s still-life is compositionally similar to another work on display, Laura Letinsky’s “Untitled #38;” and it draws on a similar tradition of bourgeois parlor painting that the marble bust of Andrew Moore’s “Casa Vereniega, Galeria, Havana” evokes.

Girl Writing an Affidavit, 1997. Cibachrome print. © Tom Hunter, courtesy of the artist, and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York

But Hernandez’s subject is an explicit lack of physical home, an environment of misery (unlike the dreamily-aestheticized temporary home in Kurland’s image) that comes from being deprived of such a place. Letinsky’s table-setting connotes a higher level of material—perhaps middle-class—comfort, but a similar level of uncertainty disorder to the scrappy “homeless landscape;” she evokes a sort of domestic unrest. Moore’s more traditional piece takes the material environment to an economic level perhaps akin to Shulman’s dystopian opulence, and yet also insinuates a warmth—a family legacy, a certain rootedness in the dense garden outside the creaking French doors—that makes this place look, and perhaps even feel, more like a “home” than Letinsky’s or Shulman’s settings.

The subject matter on display in “Notions of Home” varies, and a single visit to Yancey Richardson may not suffice to unearth the commonalities that these images share. But perhaps that is the intention of such a multi-era, multi-background group show: to evoke “notions,” rather than to impound a message. After a bit of reflection, the message seems to take shape—home, like the answers we give to that eternal “Where are you from,” is a collection of notions that only converge on a single physical place for the very luckiest among us.

Landscapes for the Homeless #14, 1990. Vintage cibachrome print. © Anthony Hernandez, courtesy of the artist, and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York